In the system of 214 Kangxi radicals, radical 138 (艮) is not merely a structural component of Chinese characters – it also carries deep cultural and philosophical significance in East Asian tradition. So what does radical 138 mean in Chinese, how is it written, and which Chinese characters commonly contain this radical? All of these questions will be clearly explained in the article below.

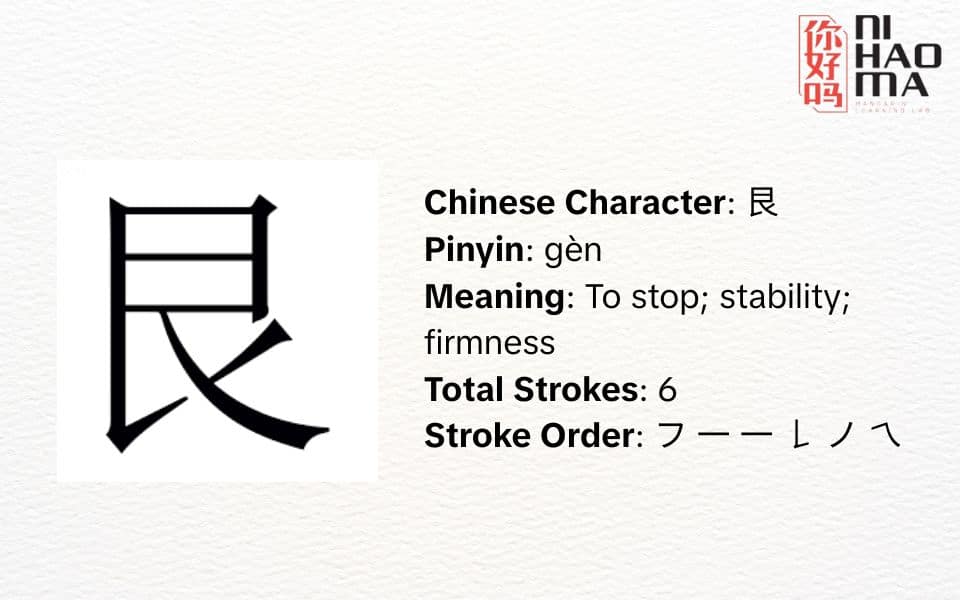

What Is Radical 138 in Chinese?

Radical 138 (艮 – gèn) is the 138th radical in the traditional Kangxi radical system. In terms of meaning, this radical is commonly associated with concepts such as stopping, stability, firmness, and restraint, and it is often used to form characters that convey these ideas.

In the I Ching (Book of Changes), 艮 (Gèn) represents one of the Eight Trigrams (Bagua) and symbolizes the Mountain. It corresponds to the northeast direction and embodies the idea of stillness, pause, and stability. The image of a mountain suggests quietness, rest, and resistance to movement. Because of this symbolic background, Chinese characters containing radical 138 often carry meanings related to boundaries, limitation, or determination.

Within the Chinese writing system, radical 138 can function both as an independent character and as a component used to form more complex characters. When combined with other radicals, it may appear in different positions within a character, directly influencing the character’s overall meaning.

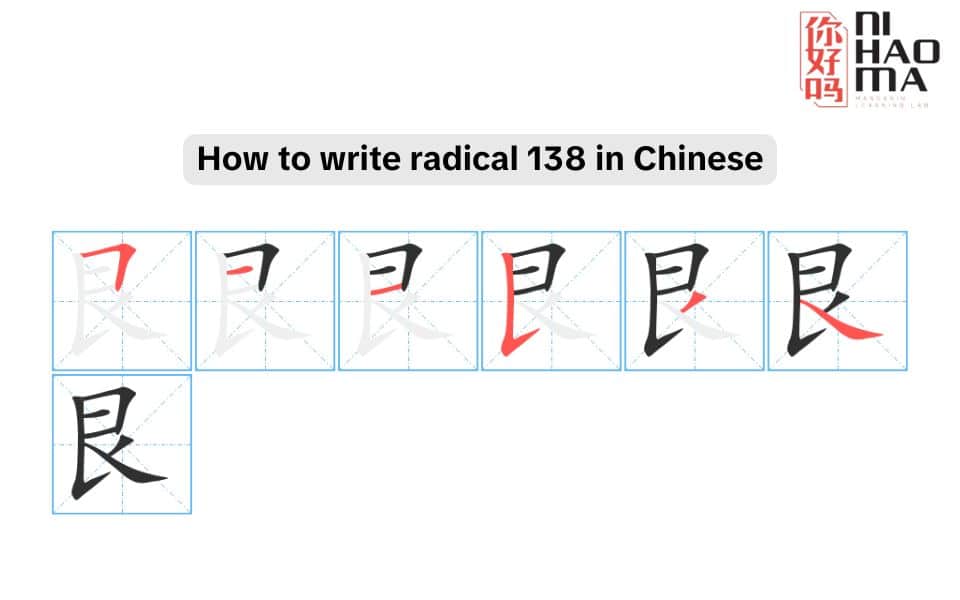

How to Write Radical 138 in Chinese

Radical 138 (艮) consists of six strokes. Writing the strokes in the correct order is essential for proper character structure and balanced handwriting.

| Stroke No. | Stroke Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 𠃌 (Turning stroke) | Write from left to right, then turn downward slightly to form the upper frame of the character. |

| 2 | 一 (Horizontal stroke) | Draw a short horizontal line inside the frame. |

| 3 | 一 (Horizontal stroke) | Write another horizontal stroke parallel to the second one, slightly longer for balance. |

| 4 | 𠄌(Rising vertical stroke) | Draw a rising stroke to create the left enclosing structure. |

| 5 | ノ (Left-falling stroke) | Write a short downward-left stroke on the right side of the character. |

| 6 | 乀 (Right-falling stroke) | Finish with a longer right-falling stroke at the bottom to stabilize the character. |

Vocabulary and Dialogues Containing Radical 138 in Chinese

In the Chinese writing system, radical 138 (艮) originally conveys the meanings of stopping, turning back, and firmness. Over time, this radical has been extended to express concepts related to degree, limitation, behavior, and state. As a result, Chinese characters containing radical 138 appear very frequently in everyday communication, especially in common spoken and written contexts.

| Chinese Character | Pinyin | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 艮 | gèn | to stop |

| 很 | hěn | very |

| 根 | gēn | root, base |

| 跟 | gēn | to follow |

| 恨 | hèn | to hate |

| 限 | xiàn | limit |

| 良 | liáng | good |

| 狼 | láng | wolf |

| 浪 | làng | wave |

| 娘 | niáng | mother |

| 粮 | liáng | grain |

| 廊 | láng | corridor |

| 朗 | lǎng | bright, clear |

| 郎 | láng | young man |

| 银行 | yínháng | bank |

| 根据 | gēnjù | basis, according to |

| 眼睛 | yǎnjing | eyes |

| 限制 | xiànzhì | restriction |

| 很多 | hěn duō | many, a lot |

| 很少 | hěn shǎo | very few |

| 退步 | tuìbù | to fall behind |

| 良心 | liángxīn | conscience |

| 浪费 | làngfèi | to waste |

| 浪漫 | làngmàn | romantic |

| 粮食 | liángshí | food, grain |

| 新郎 | xīnláng | groom |

| 女郎 | nǚláng | young woman |

| 开朗 | kāilǎng | cheerful, open-minded |

| 明朗 | mínglǎng | clear, bright |

| 有限 | yǒuxiàn | limited |

| 无限 | wúxiàn | unlimited |

| 限界 | xiànjiè | boundary |

| 根本 | gēnběn | fundamental |

| 根源 | gēnyuán | root cause |

| 狠心 | hěnxīn | cruel-hearted |

| 狠毒 | hěndú | vicious |

| 狼群 | lángqún | wolf pack |

| 郎中 | lángzhōng | doctor (traditional) |

| 新娘 | xīnniáng | bride |

| 姑娘 | gūniáng | girl |

| 退休 | tuìxiū | to retire |

| 限期 | xiànqī | deadline |

| 开垦 | kāikěn | to reclaim land |

Sample Dialogues Using Vocabulary with Radical 138

To help learners remember radicals beyond isolated characters, placing vocabulary into real communication contexts is one of the most effective learning methods. Below are several daily conversation examples using common words that contain radical 138.

Dialogue 1

A: 你最近工作很忙吗?看起来有点累。

Nǐ zuìjìn gōngzuò hěn máng ma? Kàn qǐlái yǒudiǎn lèi.

Have you been very busy at work lately? You look a bit tired.

B: 是啊,任务很多,而且时间有限。

Shì a, rènwu hěn duō, érqiě shíjiān yǒuxiàn.

Yes, there are many tasks, and time is limited.

A: 那你要根据计划来做,别太着急。

Nà nǐ yào gēnjù jìhuà lái zuò, bié tài zhāojí.

Then you should work according to a plan and not rush.

B: 我知道,可是老板很严格,限制也多。

Wǒ zhīdào, kěshì lǎobǎn hěn yángé, xiànzhì yě duō.

I know, but the boss is very strict, and there are many restrictions.

A: 别恨自己太笨,其实你做得很好了。

Bié hèn zìjǐ tài bèn, qíshí nǐ zuò de hěn hǎo le.

Don’t blame yourself—actually, you’re doing very well.

Dialogue 2

A: 时间有限,我们要先抓住重点内容。

Shíjiān yǒuxiàn, wǒmen yào xiān zhuāzhù zhòngdiǎn nèiróng.

Time is limited, so we need to focus on the key points first.

B: 对,我觉得词汇是最根本的问题。

Duì, wǒ juéde cíhuì shì zuì gēnběn de wèntí.

Yes, I think vocabulary is the most fundamental issue.

A: 那每天背一点,慢慢来,不要太狠。

Nà měitiān bèi yìdiǎn, mànman lái, búyào tài hěn.

Then memorize a little every day and don’t be too hard on yourself.

B: 好,我就跟着你的计划学习。

Hǎo, wǒ jiù gēn zhe nǐ de jìhuà xuéxí.

Okay, I’ll study according to your plan.

A: 坚持下去,效果一定会很明显。

Jiānchí xiàqù, xiàoguǒ yídìng huì hěn míngxiǎn.

Keep going—the results will definitely be very clear.

Dialogue 3

A: 现在不忙吧?出去吃点东西?

Xiànzài bú máng ba? Chūqù chī diǎn dōngxi?

You’re not busy now, right? Want to go grab something to eat?

B: 可以,我正好很想吃点热的。

Kěyǐ, wǒ zhènghǎo hěn xiǎng chī diǎn rè de.

Sure, I really feel like having something hot.

A: 那我跟你走,附近有家小店。

Nà wǒ gēn nǐ zǒu, fùjìn yǒu jiā xiǎo diàn.

Then I’ll go with you—there’s a small place nearby.

B: 好啊,吃饱就回家。

Hǎo a, chī bǎo jiù huí jiā.

Sounds good. We’ll head home after eating.

Conclusion

Through this article by Ni Hao Ma, we have gained a deeper understanding of radical 138 in Chinese and seen that it is a radical with a high frequency of use in modern Chinese. By combining stroke order, vocabulary learning, and real-life dialogues, learners can use Chinese more naturally instead of merely recognizing characters.

We hope this article has provided you with valuable insights, and don’t forget to explore more engaging content about Chinese radicals in our upcoming posts!