Chinese Calligraphy, the art of beautiful handwriting, has been revered in Chinese culture for millennia. It’s more than just writing; it’s a profound expression and communication through each stroke. Among the vast history of Chinese art, calligraphy stands as a luminous thread, woven with the delicate characters of masterful calligraphers.

Now, let’s delve into the lives and works of some of China’s most celebrated calligraphers. These individuals, through their unique styles and in-depth understanding of character, have shaped the aesthetic and cultural landscape of China and continue to inspire artists and calligraphy enthusiasts worldwide.

Famous Calligraphers Profile

Wang Dongling

Wang Dongling is currently the head of the Modern Calligraphy Study Center at the China National Academy of Arts. He graduated from the calligraphy department of the China National Academy of Art in 1981. His calligraphy works quickly gained recognition within China. This leads to solo exhibitions at prestigious venues like the National Art Museum of China in Beijing and the China National Academy of Art in 1987.

Wang Dongling bridges traditional Chinese calligraphy with modern and postmodern art concepts. He blends the physicality and expressiveness of calligraphy with abstract and conceptual ideas. Renowned as China’s foremost living influential calligrapher, he’s had an unprecedented three solo shows at the National Art Museum of China. While famous for his dynamic, cursive-script calligraphy performances, Wang is also a pioneer in experimental forms, like capturing his calligraphic movements directly onto silver-gelatin photographic paper.

Wang Dongling revitalizes traditional calligraphy by emphasizing performance and abstract expression. His large-scale calligraphy performances showcase the physicality of the art form, revealing how the artist’s body and energy shape the work. Wang Dongling’s abstract calligraphy frees the brushstrokes, shapes, and composition from the constraints of written language.

Wang Dongling considers the line to be the core element of calligraphy and believes that through experimentation and innovation, Chinese calligraphy can achieve global recognition as a universal art form. Twentieth-century art movements like Modernism and Minimalism frequently looked to calligraphy as a source of inspiration, particularly for its early exploration of expressive brushwork.

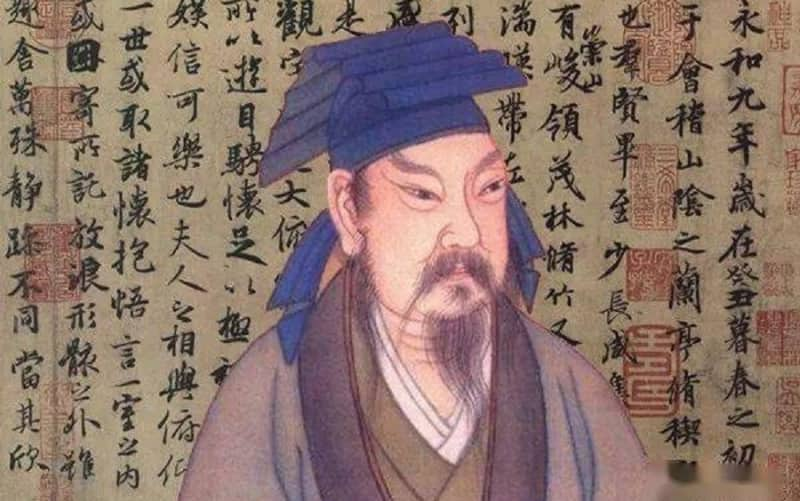

Wang Xizhi

Born in Shandong Province, Wang Xizhi spent most of his life in Zhejiang Province. He learned calligraphy from Lady Wei and became a master of all script styles, especially semi-cursive script. His calligraphy was so highly valued that even his individual characters were incredibly precious during his lifetime. Unfortunately, none of his original works survive today. Despite the loss of his original works, Wang Xizhi’s style has been meticulously copied and preserved by countless generations of aspiring calligraphers who love and adore his art.

Wang Xizhi’s most celebrated work is the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion (蘭亭集序), an introduction to a collection of poems written by a group of poets gathering at Lanting (蘭亭, Orchid Pavilion) during the Spring Purification Festival to write poetry and savor the pleasure of drinking wine. Wang Xizhi’s calligraphy was composed in the running script style, which he perfected and set the standard for this writing style. .While the original manuscript is lost to history, high-quality copies and impressions of it have been preserved.

Zhang Zhi

Zhang Zhi (張芝) also known as Boying, was a renowned calligrapher during the Eastern Han Dynasty, often hailed as the “Sage of the Cursive Script.” Son of the Eastern Han general, Zhang Huang, Zhi’s life remains largely undocumented in official histories. However, he was celebrated for his strong moral character. He also insists a disdain for worldly affairs, and a profound respect for traditional knowledge.

Zhang Zhi’s cursive script is celebrated for its dynamic, free-flowing, and natural appearance. His extraordinary talent allowed him to effortlessly create unparalleled beauty. His skill was so exceptional that even Wang Xizhi, considered the greatest calligrapher, acknowledged Zhang Zhi’s superiority in cursive script.

While cursive script is expressive and energetic, mastering it requires exceptional skill and a calm mind. Zhang Zhi understood this and never wrote his famous cursive pieces when feeling rushed. True masterpieces can only be created by those who combine technical brilliance with inner peace.

Zhang’s cursive script was not only faster to write but also more space-efficient. This was particularly beneficial in an era when writing materials were limited to narrow strips of bamboo or wood. Like many calligraphers of his time, none of Zhang Zhi’s original works have survived. Considering the materials and conditions of that era, this is not unexpected. However, there are copies of his calligraphy, these are often traced or replicated versions but considered with inferior brilliance.

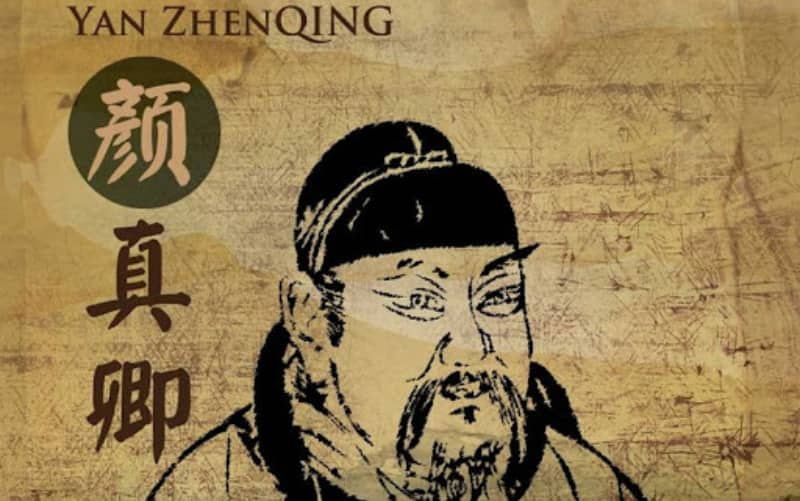

Yan Zhengqing

Yan Zhenqing (顏真卿, 709–785), a prominent figure of the Tang Dynasty, is regarded as one of China’s greatest calligraphers. His distinctive “Yan style” of regular script is a foundational model for countless calligraphy students. Renowned for its strength, boldness, and grandeur, this style elevated Chinese calligraphy to new heights.

Despite his artistic brilliance, Yan Zhenqing was also a dedicated government official. His unwavering loyalty to the Tang Dynasty, particularly during the An Lushan Rebellion, earned him great respect. Tragically, The Grand Councilor, Lu Qi, held a grudge against Yan Zhenqing due to his uncompromising nature which later led to his untimely demise.

Yan Zhenqing’s calligraphy evolved through three distinct phases. His early years were marked by experimentation and learning from masters like Zhang Xu and Chu Suiliang. During his middle age, his style matured, characterized by bold strokes and structured forms. In his later years, Yan Zhenqing achieved the pinnacle of his artistry, producing works of unparalleled mastery and emotional depth.

While celebrated for his calligraphy, Yan Zhenqing’s life was cut short due to political intrigue. His legacy, however, endures as a testament to both artistic excellence and unwavering loyalty.

Huang Tingjian

Huang Tingjian, Born in Fengning, Jiangxi province, a renowned Chinese poet and calligrapher, is respected as the founder of Jiangxi school of poetry. He achieved academic success by passing the prestigious jinshi exam in 1067, leading to a teaching position at the Imperial Academy in Beijing.

He was assigned with writing the official history of the Song dynasty emperor Shenzong in 1085. However, accusations of errors and calumny in the compilation led to his demotion and a lengthy period of exile

He and Su Dongpo are often named together as literary and artistic contemporaries. They, along with Mi Fu and Cai Xiang, are celebrated as the four most influential calligraphers of the Song Dynasty. While Su Dongpo was outgoing, He was more reserved and contemplative. This difference in personality is reflected in their artistic styles. His calligraphy was bold and spontaneous, inspired by the work of Huaisu, a Tang Dynasty monk.

Tingjian is celebrated as a highly skilled and innovative calligrapher of the Song era. His running script style, characterized by its distinct boldness and energy, is easily identified by calligraphy enthusiasts. His work, “Biographies of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru,” highlighted a technique known as “flying-white”. The technique comes from a unique brushstroke that creates broad, flowing lines resembling a leap across the paper. This is achieved in a single, continuous movement without lifting the brush.

Famous Calligraphy Pieces

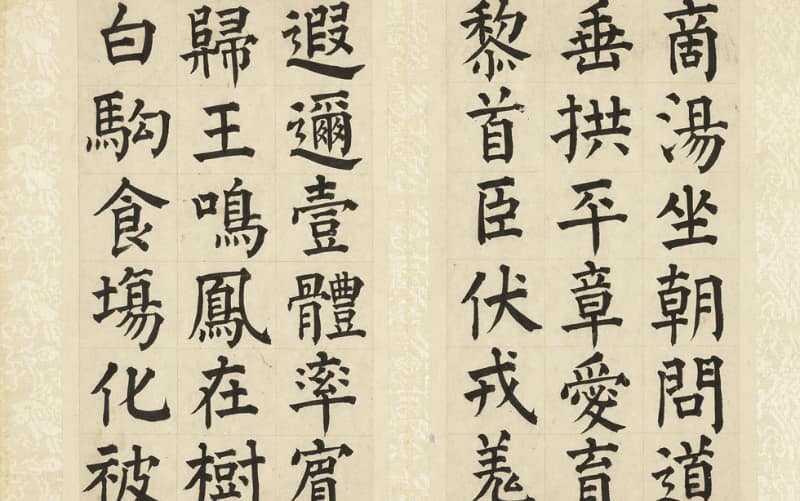

Thousand Character Classic

The Thousand Character Classic is a well-known Chinese poem that has been used to teach children how to read and write Chinese characters since the 6th century. It consists of exactly one thousand different characters arranged into 250 four-character lines that rhyme. This structure makes it easy to memorize, similar to how children learn the alphabet through a song. Together with the Three Character Classic and the Hundred Family Surnames, it formed the foundation of traditional Chinese education.

The Thousand Character Classic has been a popular subject for calligraphers in East Asia due to its extensive use and the fact that it contains a thousand different characters. The Northern Song imperial collection included 23 original works by the Sui dynasty calligrapher Zhiyong, 15 of which were copies of the Thousand Character Classic. Many famous Chinese calligraphers, including Chu Suiliang, Sun Guoting, Zhang Xu, Huaisu, Mi Yuanzhang, Emperor Gaozong of Southern Song, Emperor Huizong of Song, Zhao Mengfu, and Wen Zhengming, created notable calligraphic versions of the poem.

Discovered among the ancient manuscripts of Dunhuang, practice fragments of the Thousand Character Classic provide evidence that using the poem as a calligraphy exercise was common practice by at least the 7th century.

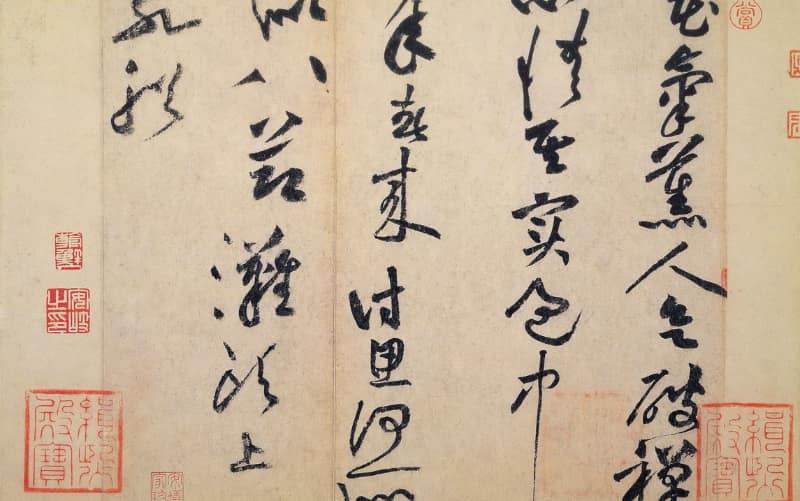

Flower’s Fragrance

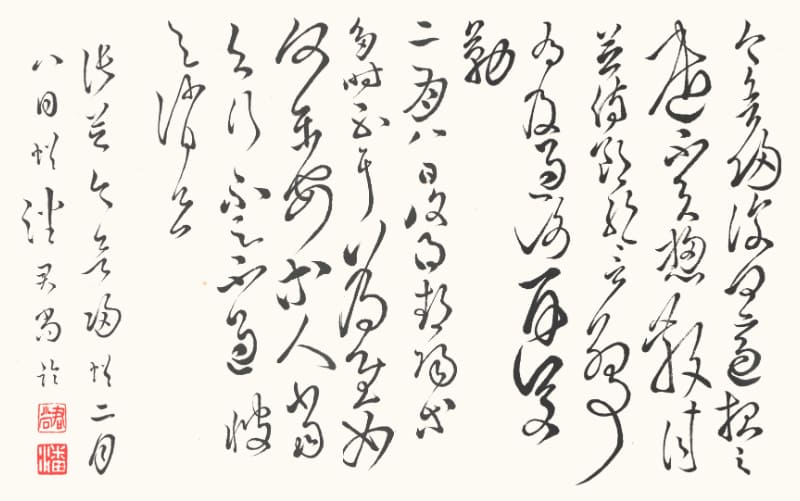

Huang Tingjian, a renowned Song Dynasty calligrapher, wrote a poem titled “Flowers’ Fragrance” as a playful response to his friend Wang Gong’s persistent requests for poetry. Despite his friend’s eagerness, Huang initially resisted writing but eventually gave in due to the constant gifts of flowers he received.

The poem, written in a strong and expressive style, conveys the author’s reluctance to respond to him. The calligraphy is bold and upright, with ink tones ranging from dry and moist.

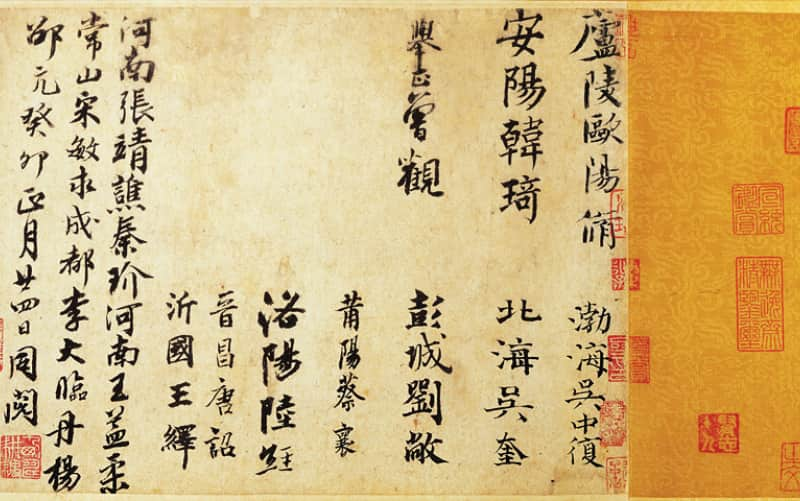

Three Passages: Ping-an, He-ru, and Feng-ju

This scroll displays three carefully copied works of the renowned calligrapher Wang Xizhi. Despite being copies, they remarkably capture the energy and fluidity of his original style. These pieces break away from traditional formal scripts, showcasing a free and expressive form that established Wang Xizhi’s reputation as a calligraphy master.

This scroll showcases three different pieces of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi, each addressed to a different person. The first piece: “Ping-an” is a message to his cousin, written in a mix of running and cursive script, expressing goodwill and care. The second: “He-ru” is a greeting to a friend, accompanied by an update on his life, written in running script. The final piece: “Feng-ju”, also in running script, is a short note included with a gift of tangerines to friends. Each piece exhibits unique brushwork, ranging from fluid and graceful to bold and decisive.

Conclusion

Beyond the technical mastery of brushwork and character formation, calligraphy offers a glimpse into the artist’s soul. Each stroke reveals a unique personality, capturing emotions and narratives through the dance of ink on paper. The beauty of this art form lies not only in its visual appeal but also in its ability to connect us to the past, offering a bridge between history and contemporary artistic expression.