Chinese calligraphy, s referred to as shūfǎ or fǎshū (書法/书法, 法書/法书) is a visual art form first rise to prominence in the Han Dynasty (206BCE-220 CE). It marks marking a cultural touchstone that has captivated China and influencing the world for millennia.

Even today, echoes of many ancient scripts can be seen in modern Chinese writing. Get ready to travel through the history of Chinese calligraphy! We’ll see how it transformed from ancient pictograms to the diverse styles practiced today.

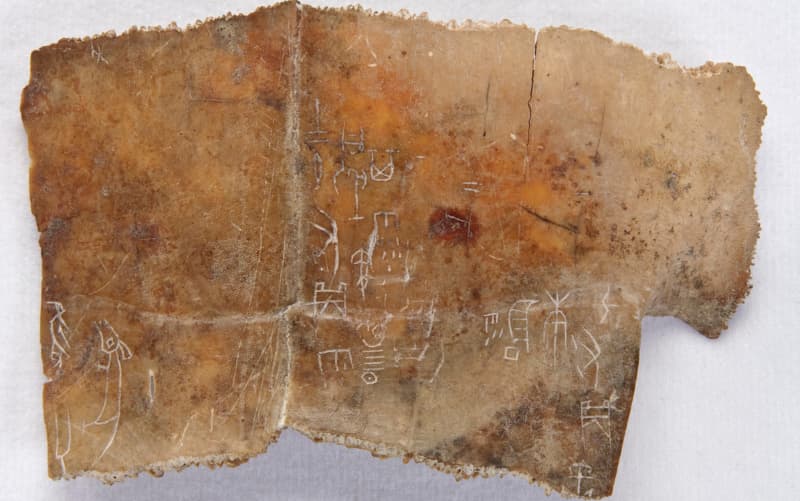

Origins of early Chinese characters & writings

Earliest known Chinese logographs

The earliest known Chinese logographs, dating back to the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE). These characters, etched on animal bones or tortoise shells, also known as jiaguwen, or oracle bone inscriptions.

The writings found on oracle bones predominantly consisted of inquiries directed towards ancestors or deities and their corresponding responses.

Concept of tools and materials used at early stage

The Zhou Dynasty witnessed substantial societal and political transformations that had a profound impact on the evolution of writing. It was during this era that calligraphy began to emerge, with brush and ink becoming the primary tools.

When comparing the oracle bone script to the writings found on Shang and early Western Zhou period bronzes, noticeable differences arise. The oracle bone script exhibits a significant simplification, often converting rounded shapes into straight lines. This alteration is attributed to the difficulty of engraving on the hard surface of bones. Conversely, the more intricate and pictorial nature of the bronze inscriptions better reflects the typical writing style of the Shang Dynasty, particularly as seen in bamboo writings, rather than the oracle bone script. This particular style continued to evolve into various writing styles during the Western Zhou period.

Evolution of Materials and Tools in Chinese Calligraphy

The evolution of calligraphy wasn’t just about the characters. The tools and materials used by calligraphers also played a crucial role.

Brush

The invention of the brush around 300 BCE revolutionized writing. Calligraphy utilized highly flexible brushes made from animal hair or occasionally feathers, which were shaped to a tapered end and attached to a handle made of bamboo or wood.

Ink & inkstick

Writers prepare their own ink by grinding inksticks on an inkstone. Inksticks were usually composed of soot, derived from burning pine wood or other plant materials, combined with glue or animal substances to blend it together. By adding a small amount of water, the inkstick was ground against the inkstone, producing black ink with different thicknesses. The act of grinding the inkstick was regarded as an artistic practice, and accomplished calligraphers paid meticulous attention to the preparation of their ink.

Paper

The main mediums used for writing included wood, bamboo, silk (from approximately 300 BCE), and later paper (from around 100 CE). Calligraphic creations were not limited to dedicated writing surfaces but could also be found on common objects. Among these options, paper emerged as the favored material for calligraphy. The introduction of superior-quality paper, credited to Cai Lun in 105 CE, significantly contributed to the advancement of more artistic calligraphic styles. Paper’s absorbent qualities allowed for the meticulous capture of every nuanced brushstroke variation.

Calligraphy Script Styles & Technique Development

There were five main scripts in ancient Chinese calligraphy:

- Seal script (zhuan shu)

- Clerical script (li shu)

- Regular script (kai shu, zhen shu or zheng shu)

- Running script (xing shu) & Cursive script (cao shu)

Seal script (zhuan shu)

The earliest form of calligraphy in ancient China was referred to as “seal script” (篆書 – zhuan shu). It featured distinct angular and structured forms. Seal script was primarily used for inscriptions on seals and official documents.

This style employed strokes of consistent thickness and minimized direction changes, facilitating easier reproduction by carvers. Seal script evolved naturally from the script used during the Zhou Dynasty. Over time, the Qin variant of seal script became the standard and was officially adopted as the formal script throughout China during the Qin Dynasty.

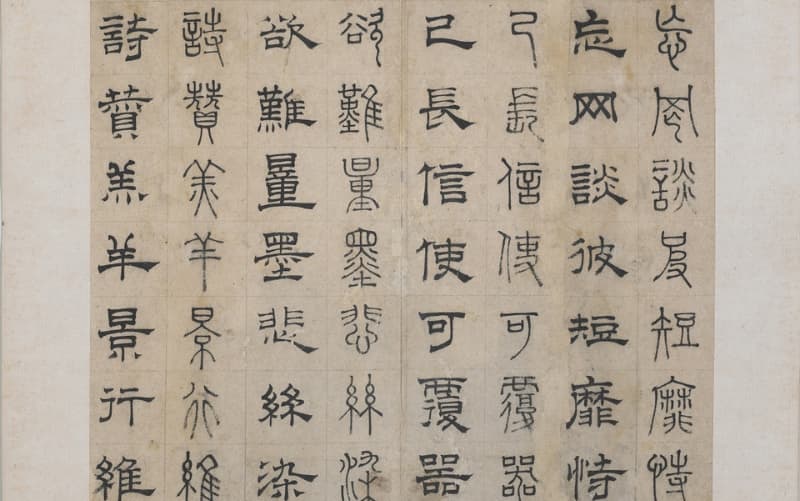

Clerical script (li shu)

The term “li” in Chinese refers to a “petty official” or “clerk.” The Clerical script, characterized by its distinctive heavy stroke endings, was a formal script primarily employed for record-keeping by clerks and officials. Subsequently, it became commonly used for inscriptions.

A close look of li shu reveals a scarcity of circles and curved lines. Instead, squares and short straight lines, both vertically and horizontally, are prevalent. The nature of writing in clerical script required speed and constant up-and-down hand movement that made achieving a consistently even line thickness challenging.

During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), Clerical script gained prominence and became the prevailing form of writing widely utilized for administrative purposes.

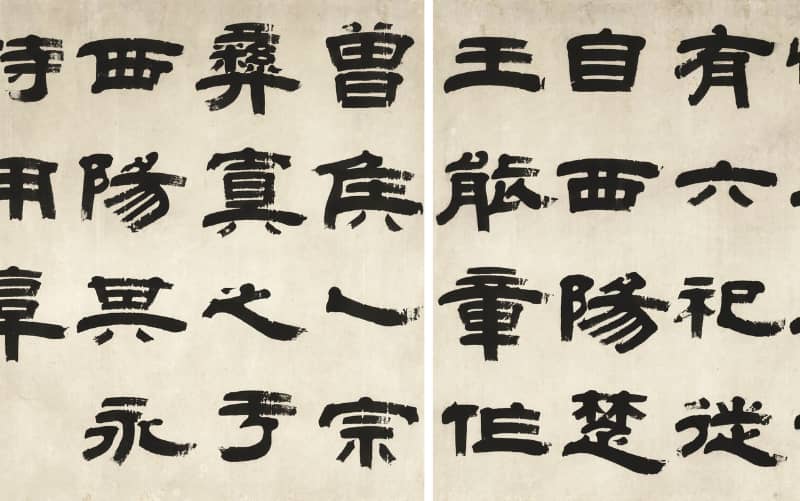

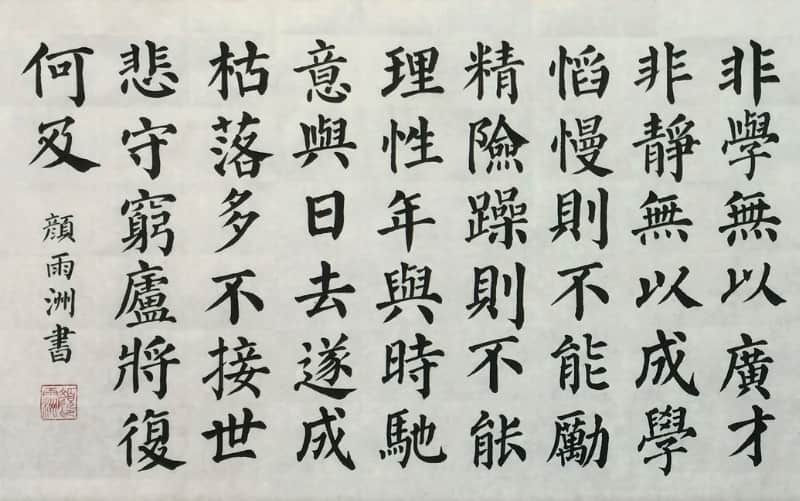

Regular script (kai shu, zhen shu or zheng shu)

The li shu style of writing is characterized by square or rectangular words with a wider width than height. Although stroke thickness may vary, the shapes maintain a rigid structure. This constraint limited the freedom of individual artistic expression, leading to the creation of zhen shu (kai shu), also known as regular script. The exact originator of this style is uncertain, but it likely emerged during the Three Kingdoms and Xi Jin period (220-317).

Regular script, which developed during the Han Dynasty, served as a simplified and more legible form of clerical script. It was widely adopted by the Chinese for government documents, printed books, and significant public and private transactions. Remarkably, the Chinese continue to write in regular script today. In essence, modern Chinese writing has roots that date back nearly 2,000 years, and the written language of China has remained unchanged since the first century of the Common Era.

From the Tang period (618-907 CE) onwards, it became mandatory for every candidate participating in the civil service examination to possess the ability to write in regular script. This imperial decree had a profound impact on all aspiring Chinese scholars and individuals aspiring to enter the civil service.

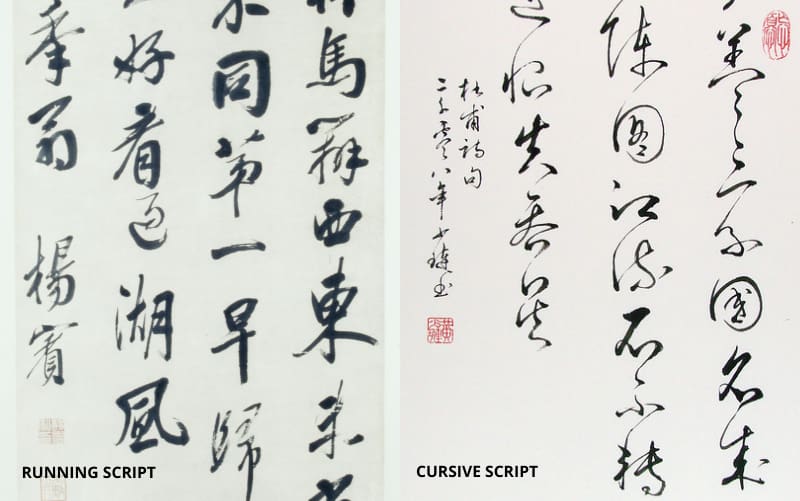

Running script (xing shu) & Cursive script (cao shu)

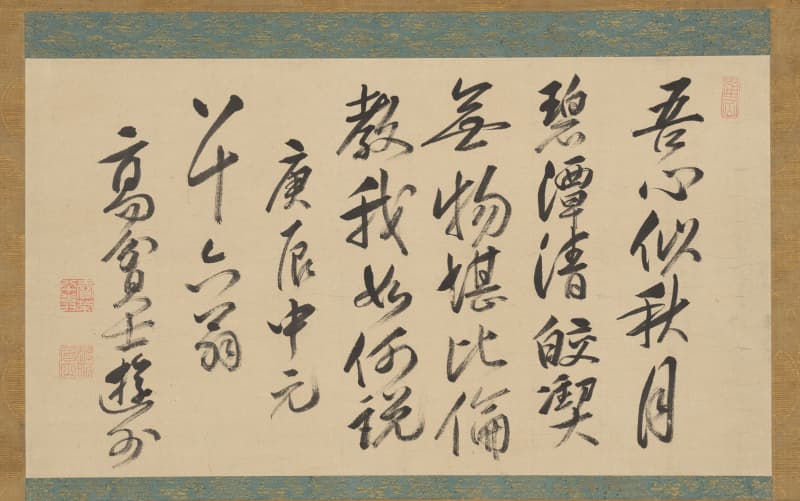

During the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317-420 CE), another notable calligraphic style emerged known as “running script” (xingshu). Running script was distinguished by its rapid and fluid strokes, making it highly favored for informal writing, personal letters, and poetry. It marked a departure from the rigid structure of earlier scripts, enabling greater artistic expression and individuality.

Lastly, there is caoshu, which is sometimes referred to as Cursive script. It acquired this name because it was the fastest script to write and possessed an unconventional quality. Artists pushed the boundaries of convention in caoshu, stretching them to their limits. As a result, some characters became challenging to recognize immediately due to the artist’s bold and expressive style.

Influence of Chinese Calligraphy on other art forms

Initially limited to the elite and scholars, calligraphy gradually permeated various segments of society, eventually becoming an essential component of Chinese education and culture. Writing with brush and ink became a symbol of refinement and elegance, and those skilled in calligraphy were highly respected for the mastery of this art form.

The influence of brush and ink writing extended far beyond calligraphy itself. It left a lasting impact on the evolution of other artistic expressions, including painting and poetry. The techniques and aesthetics employed in calligraphy influenced and shaped these art forms, further enriching Chinese artistic traditions.

Painting

The art of painting was profoundly shaped by the techniques and conventions of Calligraphy writing. Artists leverage dynamic and powerful brushstrokes, their spontaneous execution, and their skillful use of variation to create an illusion of depth. Calligraphy skills also influenced painting through the emphasis placed on composition and the strategic utilization of empty space.

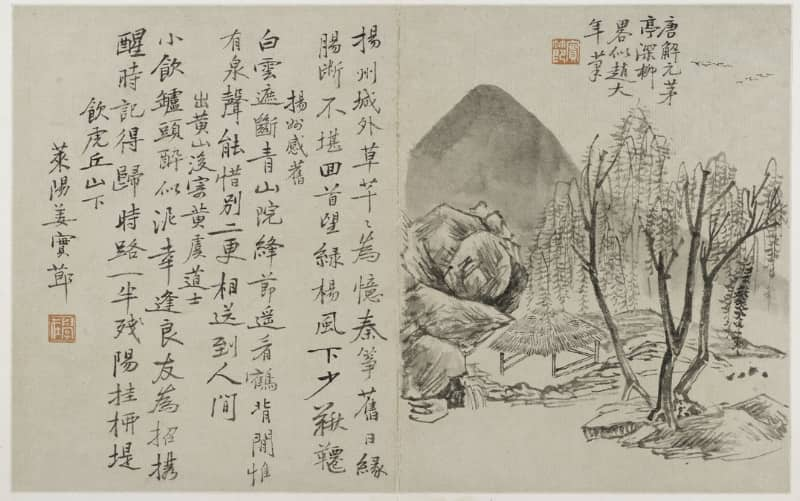

Calligraphy’s enduring significance led to its integration into paintings, serving multiple purposes. It provided descriptions and explanations of the depicted scenes, denoted the artwork’s title (although not all paintings were titled by the original artist), documented the place of creation, and indicated the intended recipient. Over time, these written elements, including notes and even poems, seamlessly harmonized with the overall composition, becoming an inseparable and integral part of the painting itself.

Poetry

In the realm of poetry, calligraphy played a vital role in shaping the visual representation of written verses. Poetic compositions often embraced a calligraphic style that complemented the tone and themes of the poems.

This convergence of calligraphy and poetry created a captivating interplay between the written word and its visual embodiment. The intricacies of calligraphic styles, such as the boldness of strokes, the delicacy of curves, and the balance of negative space, became integral elements in conveying the intended emotions and messages of the poems.

Each brushstroke carried the weight of the poet’s intent, adding depth, texture, and visual allure to the written verses. The integration of calligraphy and poetry brought about a harmonious fusion of visual and literary arts, heightening the overall aesthetic journey.

Sutra copying

Moreover, the practice of brush and ink writing played a pivotal role in safeguarding and spreading Chinese culture. It facilitated the reproduction of significant literary works, including classics and religious scriptures, thereby ensuring their enduring existence across generations.

In ancient China, devoted monks painstakingly transcribed Buddhist sutras using brush and ink, serving as custodians of these profound teachings, and ensuring their preservation for the benefit of future seekers of wisdom.

Conclusion

While computers and digital communication dominate modern life, calligraphy retains its cultural significance. The influence of Chinese calligraphy has resonated strongly in neighboring countries, shaping the development of unique calligraphic sensibilities and styles. Japanese calligraphy, for instance, has absorbed Chinese influences while also incorporating its own native scripts, such as hiragana and katakana. This fusion of Chinese and Japanese calligraphic traditions has given rise to a distinctive artistic expression.

Embracing Chinese art, history, and traditions not only enriches the Mandarin learning process but also broadens your horizons. ECA calligraphy sessions provide a unique opportunity to engage with this ancient art form, allowing learners to wield the brush and ink themselves, and experience this lively art form.