Chinese characters form one of the most complex writing systems, featuring numerous characters with similar shapes, which can often lead to confusion for learners. In this article, Ni Hao Ma will guide you through effective methods to distinguish similar Chinese characters, helping you avoid mistakes in their usage.

How to Differentiate Similar Chinese Characters

Chinese characters constitute a highly intricate system with thousands of characters, many of which share similar appearances. However, several techniques can be applied to differentiate them easily:

Analyzing Radicals

Radicals are essential components of Chinese characters and provide insight into their fundamental meanings. Many characters may share similar radicals but convey entirely different meanings; thus, recognizing radicals can help distinguish them.

Example:

日 (rì) vs. 曰 (yuē): Both characters have a rectangular shape, but 曰 has an additional horizontal stroke on top. Identifying radicals enables a clearer distinction between them.

Observing Stroke Count and Stroke Order

One of the simplest ways to differentiate similar characters is by counting the strokes and noting the stroke order. Many characters differ by only one or two strokes, making them confusing if not carefully observed.

Example:

未 (wèi) vs. 末 (mò): These characters appear similar, but the top horizontal stroke in 末 is longer than in 未.

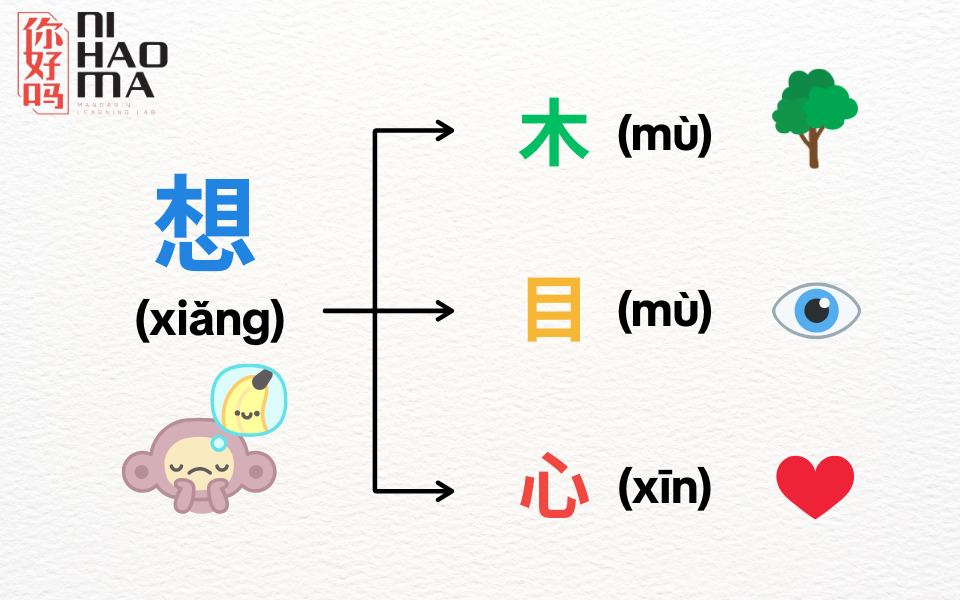

Mnemonic Devices and Visual Associations

Another effective learning technique involves using mnemonic devices and visual associations. Creating stories or images related to characters can facilitate easier memorization.

Example:

木 (mù – tree) vs. 本 (běn – root, fundamental): The character 本 is identical to 木 but includes an additional horizontal stroke at the bottom, symbolizing the tree’s root. This can help recall that 本 represents “origin” or “foundation.”

Commonly Confused Character Pairs

Distinguishing between similar-looking Chinese characters not only improves reading and writing skills but also enhances vocabulary retention. Below are some frequently confused character pairs and methods to identify them.

人 (rén) vs. 入 (rù)

The character 人 (rén – person) has a longer left stroke, while 入 (rù – enter) has two more symmetrical slanted strokes. Imagine 人 as a standing person and 入 as someone stepping into a place.

土 (tǔ) vs. 士 (shì)

士 (shì – scholar) has a longer top horizontal stroke, creating a balanced, upright look representing a learned person, whereas 土 (tǔ – earth) has a longer bottom stroke, symbolizing a solid, wide ground.

口 (kǒu) vs. 囗 (wéi)

口 (kǒu – mouth) is a small square, resembling an open mouth, while 囲 (wéi – surround) is a larger square enclosing space, representing the idea of surrounding or enclosing an area.

未 (wèi) vs. 末 (mò)

The character 未 (wèi) means “not yet” or “has not happened yet,” commonly used to express states that are incomplete, not achieved, or have not yet occurred. In contrast, the character 末 (mò) carries the meaning of “final” or “ending stage.”

Regarding their form, the character 未 (wèi) has horizontal strokes that are closer together, while the character 末 (mò) has a longer top horizontal stroke.

日 (rì) vs. 曰 (yuē)

The difference between the character 日 (rì – sun, day) and the character 曰 (yuē – to say) lies in the horizontal stroke inside. The enclosure of the character 日 (rì) has a vertical rectangular shape while the enclosure of the character 曰 (yuē) is shorter like 口 (kǒu).

己 (jǐ) vs. 已 (yǐ)

己 (jǐ) means self or oneself, commonly used when referring to oneself or related to the self. Meanwhile, 已 (yǐ) means already or completed, indicating an action that has been finished. If you look carefully, you’ll notice that the final stroke of the character 已 (yǐ) extends higher than the horizontal stroke, while the final stroke of the character 己 (jǐ) starts from the preceding horizontal stroke.

大 (dà) vs. 太 (tài)

The character 大 (dà) means “big,” “large,” or “great” and is often used to indicate size, degree, or significance. Meanwhile, the character 太 (tài) carries the meaning of “too,” “very,” or “excessively,” describing a state that surpasses a certain limit.

The character 大 (dà – big, large) consists of three simple strokes, whereas the character 太 (tài – too, very) has an additional small dot below.

牛 (niú) vs. 午 (wǔ)

牛 (niú – cow) has a vertical stroke extending through the entire character, resembling a cow with horns, whereas 午 (wǔ – noon) has a vertical stroke that does not extend through the top horizontal stroke.

千 (qiān) vs. 干 (gàn)

千 (qiān – thousand) has two horizontal strokes, with the top one slightly slanted, while 干 (gàn – to do) has straight, evenly spaced horizontal strokes.

今 (jīn) vs. 令 (lìng)

The character 今 (jīn – today) has a total of four strokes, with the lower part consisting of two simple strokes. Meanwhile, the character 令 (lìng – order) has a total of five strokes, with an additional slanted stroke at the bottom.

右 (yòu) vs. 石 (shí)

The character 右 (yòu) means “right” and is commonly used to indicate direction. On the other hand, the character 石 (shí) means “stone,” representing a hard and durable material. However, the key difference lies in the downward stroke (piě): in 右 (yòu), this stroke cuts through the top horizontal stroke.

木 (mù) vs. 本 (běn)

The character 本 resembles 木 but with an extra horizontal stroke at the bottom, representing the roots of a tree. You can remember that 本 means “root,” which implies “fundamental” or “origin.”

手 (shǒu) vs. 毛 (máo)

The character 手 (shǒu) means “hand,” referring to the body part used for grasping and manipulating objects. The character 毛 (máo) means “fur,” “hair,” or a small unit of measurement. The key difference lies in the lower part: in 手 (shǒu), there is a vertical stroke with a hook, whereas in 毛 (máo), there is a curved hook stroke.

小 (xiǎo) vs. 少 (shǎo)

The character 小 (xiǎo) means “small,” referring to size or a small quantity. In contrast, the character 少 (shǎo) means “few,” “lack,” or “rare.” The difference lies in the middle stroke: in 小 (xiǎo), it is a downward hook, while in 少 (shǎo), it is a vertical stroke with an additional downward slanted stroke at the bottom.

天 (tiān) vs. 夫 (fū)

The character 天 (tiān) means “sky,” “nature,” or “day.” The character 夫 (fū) means “husband” or “man.” The main difference lies in the third stroke: in 夫 (fū), the vertical stroke (丨) cuts through the second horizontal stroke, while in 天 (tiān), the vertical stroke (丨) is positioned below the two horizontal strokes.

师 (shī) vs. 帅 (shuài)

The characters 师 (shī – teacher, master, strategist) and 帅 (shuài – handsome, commander) both contain the radical 巾 (cân), but they differ in the top-right part. The character 师 (shī) has a total of five strokes, while 帅 (shuài) has only four strokes and lacks the horizontal stroke on the right side.

学 (xué) vs. 字 (zì)

Both characters 学 (xué – to study) and 字 (zì – character, word) have similar strokes, which can cause confusion at first glance. However, the top part of 字 (zì) contains the radical 宀 (mián), while the top part of 学 (xué) consists of the radicals 小 (xiǎo) and 冖 (mì).

季 (jì) vs. 李 (lǐ)

The characters 季 (jì – season) and 李 (lǐ – plum tree) may look similar at first glance, but when broken down into radicals, there is a clear difference. The character 季 (jì) is composed of the radicals 禾 (hé) and 子 (zǐ), while the character 李 (lǐ) is made up of the radicals 木 (mù) and 子 (zǐ).

狠 (hěn) vs. 狼 (láng)

The characters 狠 (hěn – fierce, cruel) and 狼 (láng – wolf) are two Chinese characters that have the same radical but are easily confused. The difference lies in the right part of the two characters: 狠 (hěn) has the character 艮 (gèn), while the character 狼 (láng) has the character 良 (liáng).

Conclusion

Distinguishing similar Chinese characters can be challenging, but by analyzing their structure, stroke order, and components, learners can recognize their differences more easily. We hope this article by Ni Hao Ma has provided valuable insights and practical techniques to help you effectively memorize and differentiate these often-confusing Chinese characters.